An exhibition of work by artists and makers based out of Inverness Creative Academy.

Stop by Inverness Creative Academy to see a showcase of the amazing work that is made at this creative hub for the Highlands. The participating artists are also hosting an Open Studios event on Saturday 12 May (10am-4pm) which you are invited to. Don’t miss the rare opportunity to get a glimpse of working artists’ studios.

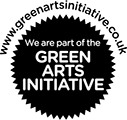

Fiona Hutchison and Joanne Soroka are two prominent tapestry weavers who are showing new work at the Patriothall Gallery this May. While women’s art, and in particular textiles, has historically been sidelined by mainstream culture, today it is increasingly valued and celebrated.

Based on her own experience of sailing, Fiona’s work is inspired by all things maritime, enhanced by poetry and literature on the subject. She works primarily in tapestry but also in paper and recycled plastics, drawing the maximum from these media in two and three dimensions.

Inspired by her diverse ancestors, Joanne’s work reflects on the places they came from and their journeys as migrants to new and unknown lands. More recent work looks at the plight of refugees and the hazardous migrations of birds. She uses rich colours and textures to highlight these themes.

The two textile artists have both exhibited internationally, with their work held in public and private collections.

Each artist has a unique voice, but there are also many points of contact in their concerns and interests. Like weaving itself, the work is often about connections which are the strongest ties.

Born in Edinburgh, Fiona Hutchison is an artist and teacher working in tapestry and mixed media. Having graduated from Edinburgh College of Art with first class honours, then a postgraduate diploma (with distinction), she has gone on to travel the world promoting Scottish tapestry. She has networked with tapestry artists through attending symposiums in Lithuania, Russia and South Korea, participated in artist residencies in Norway and Scotland, and has taught across the USA with the American Tapestry Alliance. A professional member of the Society of Scottish Artists, she exhibits in solo and group shows at home, in Europe and across the world. She is a founding member of the European Tapestry Forum and STAR* (Scottish Tapestry Artists Regrouped).

Joanne Soroka was born in Montreal and graduated from McGill University, the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and Edinburgh College of Art, leaving with a post-graduate diploma (with distinction). She was the Artistic Director of the Edinburgh Tapestry Company (Dovecot Studios), before setting up her own studio in Edinburgh in 1987. She makes tapestries, other textiles and paperworks, with occasional forays into other media. Her work is in the collections of museums, well-known companies and hotels. She has won numerous awards. Joanne has exhibited around the world, with over a hundred group shows and eleven solo shows in twenty countries. She is the author of Tapestry Weaving: Design and Technique, now in its seventh printing.

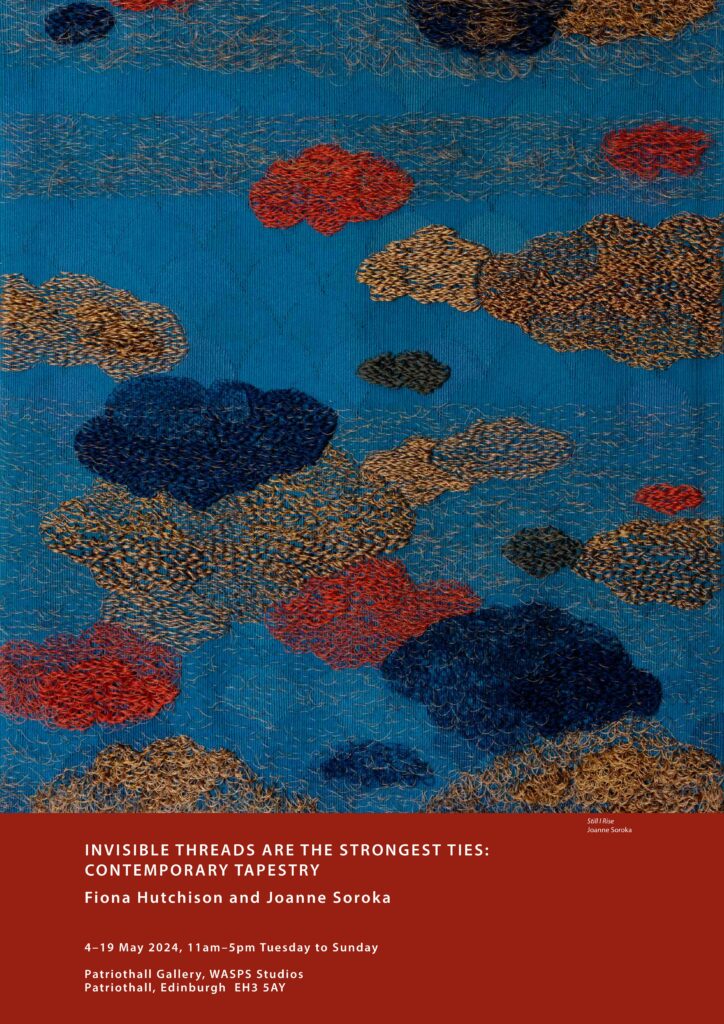

A joint exhibition with artists Rosie Vohra and Gabrielle Lockwood Estrin, building on their decade-long dialogue through collaborative collage practice, exploring connection, growth, and belonging.

Hand

Over is a collaborative exhibition by artists Gabrielle Lockwood Estrin and Rosie Vohra. The exhibition explores collage as a process and principle that is inextricably linked to human connection, growth and sustainability. Through reusing existing materials and reshaping them, they create a new body of work that addresses themes of absence, presence, connection, and belonging.

The heart of their collaboration lies in a continuous exchange of drawings, collages, and paintings, either through post or in person, spanning many years, life events, and locations. This ongoing dialogue forms the basis of their creative process, where each work responds to the last, fostering a conversation of back and forth. By relinquishing control to each other for each iteration of the exchange, they embrace play as a central element, allowing for the unexpected to enrich their collaborative dialogue.

Their collaborative process embodies a playful exploration of rupturing, reforming, and repurposing old works as they create new connections and meanings, rooted in their shared understanding of the themes they explore. This collaborative endeavour, rich with the depth of each artist’s perspective, invites viewers to engage with the work on multiple levels.

Rosie Vohra is a multidisciplinary artist working and living in Leeds. Vohra explores the intersection of collage with drawing, painting, textiles, and sculpture. She uses collage as both a conceptual and material tool for deconstructing and reconstructing meaning from existing material. Her work often explores collective storytelling with personal introspection, offering insights into the complexities of human existence and the process of identity formation. Through her work, Vohra advocates for openness and the potential for metamorphosis, providing a framework for embracing multiplicities.

Gabrielle Lockwood Estrin is an artist and arts educator based in Glasgow. Through painting and printmaking she explores the relationships between our internal and external worlds. Her visual language gives colour and form to emotions and experiences, exploring how these manifest and shift in our bodies as we navigate environments, relationships, and changes around us.

Often working on collaged surfaces of paper or fabrics with a previous history – creating structures from old drawings and monoprints – her layered shapes interact and undulate, mapping internal journeys. Negative and positive spaces reflect absence and presence: reliant on each other, they can only exist through an experience and memory of each other. Her work gives shape to the spaces created by loss, and explores what grows from and within them.

Rosie Vohra (b.1992, Hertfordshire) lives and works in Leeds. Vohra studied on The Drawing Year at The Royal Drawing School in 2014 where she was awarded The Sir Denis Mahon Award 2013. Prior to this, she studied Fine Art at Leeds Arts University from 2010-13. Recent solo and duo exhibitions include: Fruiting Bodies, Leeds Arts University, 2023; Flying Inside Your Own Body, Slugtown, Newcastle, 2023; WORMB, Quench Gallery, Margate, 2022; Canopy Kilt, Proudick Gallery, London 2019. Recent group exhibitions include: Leeds Artist Show, Leeds Art Gallery, 2023; The Amber Room, Matt’s Gallery, London, 2023; Post Curse, Freehold Projects Space, Leeds, 2019; Social Event, Platform, Glasgow International Festival, 2018. Vohra’s work is held in public and private collections including: The Government Art Collection, The Royal Collection, Hauser and Wirth and Leeds Art Gallery Collection

Gabrielle Lockwood Estrin (b.1987, London) lives and works in Glasgow. Lockwood Estrin graduated with Honours from Glasgow School of Art in 2010, she received the Armour Award for drawing and painting, and was later awarded a scholarship for postgraduate study at the Royal Drawing School in London. Following this, she completed a two year printmaking fellowship at City and Guilds of London Art School. She has also studied at the Instituto Superior de Arte, Havana. She has exhibited widely in London, Berlin, Havana, Glasgow, Edinburgh and around the UK and has been awarded artist residencies in Scotland, Venice, America, and Cuba, including a residency at the Women’s Studio Workshop in NY in 2020. Most recently she had a solo show: Mapping The Parts, at Mono8 Gallery in Manila, Philippines, 2023, was artist in residence with 16Nst Gallery in Glasgow and was commissioned to make a new work for the exhibition and publication Rupture, Rapture: Womxn in Collage exhibited at Patricia Fleming Gallery, 2023.

Showcasing iconic woodland types from the Highlands that have clung on to inaccessible topographic margins. A feast of colour, pattern, texture, botanical detail and atmospheric places.

Arboreal Realms showcases the character of some of the most iconic woodland types in Highland, with surviving remnants often clinging to inaccessible topographic margins. From 2 years’ work, over 60 compositions are a distillation of wooded places, pattern, colour, textures, seasons and atmospheres at both the macro and micro scale ranging from realistic portrayals to more stylised abstractions in both oil and acrylic. The allure, shelter, scale and detail of woodland is endlessly rekindled at the turn of each season; whether clad in leaf or laid bare, trees emanate a strong and often distinctive localised Highland identity. Broadly two differing Arboreal Realms are explored:

• Pine, Birch and Juniper woods known as Caledonian Pine Forest (plus plantations) over peaty acidic soils with heather, bilberry, grass and sometimes localised bog underneath

• Oak, Birch and Hazel woods over deeper brown earths with bracken or grassland and spring vernal flora underneath. There are also a few forays into damper woods with more base loving plants.

With the high rainfall that the west coast, montane and inland gorge topographies receive, rich assemblages of lichens, mosses and ferns grow on the trunks, ground and rocks of these woodlands, forming what have poignantly recently been renamed part of Britain’s Lost Rain Forests. Many remnant native woodlands have struggled to regenerate since deer, sheep and rhododendron replaced people managing woods locally. Fortunately the hard work of rewilding and reforestation initiatives offer a more optimistic future for native woodlands across Scotland; this exhibition aims to raise interest and awareness.

I want these woodland-themed paintings to make the viewer feel immersed in arboreal realms; to be in awe of places where trees, which span several human generations are allowed to colonise and regenerate, to grow and age and to rest as dead wood that supports other life. Beneath vast aged protective tree canopies is a wealth of intricate detail, connectivity and hidden history that observing closely can heighten senses, helping one to feel grounded and refreshed. I hope paintings convey my reverence for the intricacies and inter-dependencies of nature and its tenacity to cling on, adapt and thrive alongside human influence. The surety of turning seasons is hopeful and inspires me. Woodland and coast are my go to sanctuaries; immersion in the interconnections of systems seemingly beyond human control, and painting them lifts me. I hope the viewer may feel similar respite and resonance.

In 2023 my work received a commendation at the Scottish Fine Art Awards and was also shortlisted for the Highland Art Prize. This year, I am concentrating on two solo exhibitions and building collaborations linked to my arboreal artwork. – Liz Green

Born in 1964, I am a self-taught contemporary landscape painter working in oils, acrylics and mixed media. I have lived in Inverness since 2003, painted part time since 2010 and fulltime since January 2023 when I moved into a shared studio space at Wasps Inverness Creative Academy. As a person that loves being outdoors I paint the places where I have felt most keenly alive, most inspired, fulfilled and moved. I try to capture that mood of being exposed and immersed in a landscape with all the thoughts and feelings that provokes. Working in the studio based on field sketches, photographs, imagination and process-led experimentation my paintings include a mixture of realistic detail and stylised abstraction, often doing several versions of the same composition increasingly simplified and stylised. As well as meaning, I get excited by pattern, texture, form and my painting style is constantly evolving. My previous life strongly informs my art. With a degree in botany and a career as a plant ecologist (nee E.A.Cooper) working with the Conservation Agencies and NGOs I have a deep understanding of semi-natural ecosystems. Working as an environmental policy campaigner gave me an acute awareness of the value and jeopardy of semi-natural habitats. Doing garden design work to suit places and people, then working at Culloden Academy embedded my interest in visual communication and narrative. It was worsening arthritis that propelled me to start painting more back in 2010. I have not looked back and have a huge amount in my head that I still want to explore with paint.

Liz Green’s website / Liz Green’s Instagram

April is the 2023 recipient of the SSA x Wasps Award, with the prize being a solo exhibition at The Briggait in Glasgow. In Beyond the Surface, April explores the inherent agency of her surrounding rural landscape, manifested through the transient nature of both its animals and materials.

My work is an abstract exploration of landscape and of the processes I observe within it. It is figurative, colourful and highly gestural.

I live in a rural town placed between Glasgow and Edinburgh, which holds a rich industrial heritage, situated off of the River Clyde. My practice is rooted in painting and sculpture, exploring these moments in nature of collapse, of renewal and regeneration, of land ownership & place making.

I paint large-scale canvases using acrylics. Acrylic paint can be a challenging medium, it dries fast so you need to react. A comparison I like to make is between painting to this scale and feeling intimidated by the force of nature. Quite often I am hiking and the weather turns or I am caught in a storm, there is a tension and a weight to these frames which sparks questions of body and agency that my smaller works don’t.

Quite often, I am masking off, I am painting and repainting areas of the canvas. The surface of the work is layered with a lot of information, finding this balance is something I am still very much exploring, as at one stage, the abundance of information can crumble into a sea of nothing. So there needs to be this blank space, which collapses and coexists with the other side.

Quiet retellings of landscape exist within my work, small moments that perhaps would otherwise go unnoticed. The animal wool caught up in the barbed wire, the brightly coloured rope binding together specific objects.

In Sculpture and Environmental Art, at GSA, we regard context as half of the work. Yet perhaps artistic situation is half of practice.

My exploration of my rural situation in Lanarkshire, contrasted by my time of study in the built city of Glasgow, makes for a rich feeding ground of information for my practice.

April is a Glasgow based contemporary artist working predominantly through sculpture and painting. She studied a BA(Hons) in Fine Art, Sculpture and Environmental Art & most recently a Master of Letters in Fine Art, Sculpture & Performance, at the Glasgow School of Art. Her recent exhibitions include work shown at: The Royal Scottish Academy, House for an Art Lover, French Street Gallery, Wasps South Block & the McLaurin Gallery.

An artist’s take on Victorian zoologists, their textbook illustrations, love of microscopy and their curious journeys to kill and collect from the natural world.

The exhibition is loosely based around my fascination with Victorian zoologists, their textbook illustrations ( often etchings or engravings from drawings done by them selves) Their fascination with killing, catalogueing, collating, pinning, dissecting and putting under glass everything they could from the natural world around them which contrasted starkly with a simultaneously very romantic view of the same world.

Alongside these works are etchings and collaged pieces based around marine travel. The ‘curious journeys’ are however more about the period of time and the way in which all these pieces were created. The making of the artwork was a curious journey and the needle point mark making became a means of staying sane during a dark time.

Louise has been a printmaker first and foremost since graduating with a BA Hons in Printmaking in 1980s. Along with an interest in conservation and the natural world she developed her own unique style of creating copper plate etchings with a fine needle point. Following on from an artist residency at Inverewe Gardens in 2020 (which was cut short by Covid) her work moved away from almost pure illustration to more abstract themes still based very much on the 16th century methods of producing copper plate etchings. A second residency in 2023 saw her work take on a number of more defined abstract themes.

Creative Hangouts, led by visual artist Kayleigh McGuinness, is hosting their first ever community exhibition at South Block this month for one day only.

“I had this idea during lockdown to build a safe place for children to embrace their creative curiosity. A place that encouraged self-expression through accessible and playful visual art techniques. I brought this idea to life in October 2022, and since then have been delighted to work within schools and organisations offering a nurturing environment for children to process & express themselves through art. Creative Hangouts has since worked with over 500 children (and counting) to build their confidence and sense of individuality through art making processes” – Kayleigh McGuinness

The exhibition will be made up of work by the children that have participated in the workshops hosted by Creative Hangouts across Glasgow.

Visitors are welcome to stop by the show on Saturday 23 March, 1pm-3pm. The organisers will give a brief thanks to the participants, and there will be a live drawing performance beginning at 1:30pm.

Black intertidal zone inspired textiles and wood artworks symbolising concealed boundaries within self, society and stewardship.

This exhibition crosses boundaries of visual, applied and conceptual art, challenging viewers to reconsider their relationships with themselves, society, and the environment. The work draws inspiration from the black intertidal zone visible on rocks all around the world’s coastlines. This transitional area emerges and recedes with the pulse and rhythm of the tides, the pull of the sun and moon, and becomes a metaphor for the often unseen and overlooked boundaries and forces that shape our individual and collective experiences. ‘Hidden Line’ presents an exploration of these concealed, interconnected boundaries within the domains of self, society, and stewardship. Ultimately, the exhibition seeks to inspire insight, responsibility and mindfulness, challenging viewers to acknowledge and address the divisive hidden lines that may be deflecting attention from our collective psychological wellbeing, social dynamics, and environmental health.

Crafted from wool and wood, the unique, useful artworks featured in this exhibition are worthy of heirloom status. I use the hand tufting technique to paint and sculpt with yarn, weaving in elements of the natural world and heritage motifs. Each work is unique with my practice reminiscent of evolution and each finished product embodies a sense of new life.

The stools are sourced from local storm-fallen trees and crafted in collaboration with skilled woodworker Phil Crennell of The Art Vice. Phil draws inspiration from his materials and constant contact and respect for his place in nature, weaving his craftsmanship seamlessly into the narrative. Our collaboration adds layers of meaning to the works, symbolising the unseen but essential interdependence and symbiosis necessary for the well-being going forward.

In the realm of self, the textiles represent the intricate tapestry of our consciousness, interwoven with threads of personal choices, values, and perspectives. The wood with its organic and structural nature, stands as a metaphor for the innate connection between humanity and the Earth. On a societal level, these artworks highlight the veiled boundaries that enable the perpetuation of practices detrimental to our planet, with a work such as ‘Unravelling’, symbolic of the, often abolished, marks humankind has made over time and are now fraying away the health of our mother nature. The same textile, embodying the patterns of societal norms and expectations, may inadvertently contribute to a collective blindness to environmental concerns. The wood, as a structural element, simultaneously underscores other invisible foundational aspects of societal structures that often turn a blind eye to ecological crises.

These artistic expressions serve as a call to unveil and address the genuine issues surrounding the disregard for our principle mother, Earth, and all life calling this planet; according to the UN up to 1 million plant and animal species are threatened with extinction. In parallel with delving beyond the superficial boundaries depicted in the art, we confront the urgency of recognizing our collective impact on the environment, our vulnerability and overwhelming powerlessness. Simply developing better relationships with self, society, and this Earth that we all share, we will collectively increase lines of connections and holistic health and well-being.

Significantly influenced by a rural upbringing, Laura Derby (Rugaura) chose to obtain a BA Honours Degree in Industrial Design (Woven Textiles) at The Scottish College of Textiles through which her creative appreciation for colour, materials and application could develop. Working as an artisan rug maker in New Zealand inspired Laura to create her own designs and another influence has been the life and work of Friedensreich Hundertwasser; painter, architect, ecology activist and philosopher. A parallel detour into health and social care over the past 25 years has further enriched and shaped Laura’s artistic identity.

Thanks to WASPS, Craft Scotland and The Inches Carr Foundation significant milestones which have steered and informed Laura include residencies at Marchmont Creative Spaces and The Admiral’s House on Skye. Laura exhibits annually through Upland’s Spring Fling Open Studios event and features regularly in group exhibitions in Kirkcudbright. Kirkcudbright National Gallery and Buy Design Gallery in Jedburgh also stock Laura’s work.

Proudly achieving The Galloway and Southern Ayrshire UNESCO Biosphere Certification Mark acknowledges the origin and sustainability of Laura’s work, emphasising her use of 100% British Wool and upcycled local materials. This intentional choice underscores Laura’s commitment to environmental responsibility and her creations to a level of ecological integrity. In essence, Laura’s artistic journey serves as a testament to her innate connection with nature, commitment to sustainability, and the sincere desire to weave a positive thread into the fabric of life through her distinctive hand-tufted creations.

Immersing in nature evokes a sense of freedom/emotion, because landscapes are naturally occurring, and have a way of connecting with us on a deeper level.

From the artist, Cecilia Mann: Exploring my son Darren’s photography of his hillwalking and cycling has been the inspiration of this exhibition. Allowing me to investigate colour, light, structure and listening to his adventures to tell a story through my artwork. Landscapes evolving at their own pace whilst engaging with the seasons, slowly or dramatically, whilst we observe emotionally and with awe. Nature is indeed an artist shaping the mountains and landcapes, texture, shadow, contours with its never ending palette of plants, snow ice, sun, rain and everything that is natural at its fingertips. During my painting of any of the works, although I have not been on those mountains, but have been on some walks, I feel that I am there in the moment and am so absorbed with what I am painting that it becomes real for me, absorbing the atmosphere, emotion and the character of that place. Personally, I prefer not to write to much about the work, but rather leave it to the viewer to read the paintings in their own words, engaging in their own way. Similar to reading a book and then reading the same book with a different perspective each time. We all have a story to tell, which makes the process of discovery and learning an exciting journey.

From the artist, Yelena Visemirska: My most recent work is concerned with structures of lines and geometric forms. My main study is based on the invasion of industrial landscapes in natural habitats. During the creative process, I have found myself mostly drawn to the memory of places where I have been and atmospheric experiences that put a mark on my memory. We store and process our responses and thoughts, carrying them through our lives. My goal throughout this investigation of creativity was to gain a better understanding of emerging emotions and feelings towards architectural spaces that filter through my bodily experiences. Close-ups of blocks in urban spaces inform how I compose and layout my paintings. It makes me think about making the marks which represent and interpret part of space occupied by the object abstracting from location and orientation in space, size and other properties such as colour, content and material composition. I use observational photography, searching for the right tone of colours through the lens on industrial surfaces like stains, rust, and old faded paint. From soft greys, which I saw in concrete payments, I ‘adopted’ bright blue, yellow, red… The combination of contrasting tones of colours and lines brings to my work’s attention. I am working with a selected palate in which colours benefit from one another. I hope I can inspire some people to note something new around themselves. The most important and most meaningful to my work is the process itself. My next step is to look into a relationship between myself and the process of painting.

An exhibition of drawings by Janice Deary, inspired by Daoist poetry.

Spring comes and goes,

Deep in fallen flowers and streams.

People are unaware

Of all the immortals around them.

Lü Dongbin

Daoism is the philosophy of Dao, the eternal Way of nature. Daoists encourage a deep respect for the natural world and its cycles of growth and destruction. To become an immortal, one must live in harmony with the Way. Hence, some sages consider plants and animals to be closer to Dao than humans could ever be.

This project emerged out of an encounter with Daoist-inspired poetry. I work in charcoal, an appropriate medium given its connection to the natural cycle. I will also be presenting a short stop-motion animation film, based on a poem by Bai Juyi.

My artistic practice normally begins as an engagement with philosophical ideas, but at a certain point the work seems to take on a life of its own. Creation is a mysterious process: one must constantly be open to new directions and unexpected revelations. I am currently working in charcoal, a stark, prehistoric medium. I enjoy how this crude medium allows me to explore the intersection between brute material mark-making, and the emergence of meaning and beauty.

Originally from South Africa, Janice Deary is now based in Newburgh, Fife. After some time in the academic world (studying and teaching philosophy), Janice decided to pursue an MFA at the University of Dundee in 2020. Since then, Janice has exhibited her work in Scotland and Portugal.